«Architecture Sou Fujimoto»»

Von Julieta Schildknecht

This interview, with one of the most renowned 21st Century architects (and a true Japanese structuralist), is a treat for readers concerned with architecture in relation to environmental sustainability.

In 2008 Sou Fujimoto stated: “My intention was to make an architecture – referring to A House for 2 plus a Dog – that is not about space nor about expressing the riches of what are “between” houses and streets.”

Julieta Schildknecht:

How sacred are human beings to your houses?

Sou Fujimoto:

The fundament and basics of the architecture we are designing is to create a space where the interconnectedness between people as well as people and their surrounding environment can flourish. Especially in this project, House N, which is a trial to create the multiple boundaries to redefine what is an enclosure and what is a sheltering.

It is about how we can create the space for people to feel protected yet be in an open space. That is the basic and fundamental contradiction of the architectural design. We designed three layers of boxes creating blurring boundaries since I like to create a space that protects people physically as well as psychologically whilst not being a closed box thanks to its many openings and layers. People feel protected but open to their surroundings. They can choose the space and place they are sitting or lying in according to the slight but settled differences of the openness and the closeness. They can feel the distance to the sky for instance, which is always changing depending on the time and the weather. If it is a cloudy day one doesn’t recognise which layer of the box is a real boundary to the sky because the sky is also white. If the sky is blue, you can clearly see it but it is really in connection to the blue sky. If there is a blue sky with white clouds, then the cloud itself could be another layer of the architectural boundary. These extensions or curtailments create a feeling of intimacy or of openness within ones surroundings, so both nature and the human environment are fundamental. This juxtaposition isn’t only between the inside and the outside but also between the inside and other parts of the inside that create subtle boundaries. People feel good through the separations and connections. Those are the wider ranges of closing x opening and connecting x separating we are creating for people to intentionally or unintentionally choose. Such concerns for me are important fundaments which are related to cycles of human lives and human activity.

JS: How do you feel the process of creating, constructing and accomplishing a house or a building?

SF: It is an exciting challenge because from the very start we don’t know what we can achieve or make but the starting point is the conversation we have with the client and the conversation with the surrounding context as well as the historicism of the place and climate conditions… these various elements form the background of the project. We can then slowly but surely recognise the basics of the project, its essence, its heart. Once the trial process has started, we come up with different ideas and let them go. We study and engage but during the process we learn and apply forms or shapes while planning. It resembles the process of inventing or understanding anew entire things. At a certain point we feel we are reaching a significant point which might well be the idea which integrates all the contexts and ideas of the project or the scatout – the contradictions of the project. These then become well integrated. Then we feel “this is something!” Of course it isn’t only about the idea or conceptual proposal but also relates to the physical, the structural technicalities like the construction technology and materiality. From the offset we include the budget restraints?? alongside the conceptual part of the project. Finally all these details not only solve the problem but project the vision into the future. It is a journey, and an exciting one at that. Client involvement is vital, their collaboration is key and can lead to unexpected findings as well as a guarantee for a good breadth of vision.

JS: What are the similarities between House N, House Na, House H, House O and House K?

SF: Visually all of them are different. There is however a certain common ground in the very fundamental aspects of how to deal with human life and human activity, allowing for positive diversity and encouraging people to behave or live within these special fields. We built these houses in different areas, scattered yet these small areas are interconnected like a network. The meaning of each independent area is defined by itself and in relation to the other spaces. This is especially the case of House Na, which is composed of many platforms. The meaning of each platform is not predefined but the behaviour of the inhabitant on a specific platform informs the relationship with the steps above, below and around it. The space opens up to interpretation, without defining it. I feel human life should not be framed within the frame of functionality. It should be/exist beyond frames and enable people to reinterpret it on a daily basis, opening up to new discoveries in their lives. In that sense I like to create a place which allows the multiple or diverse re-understanding of the meaning of spaces. Living spaces are not only living spaces. They can be a sleeping area or the reading space. One corner of the living space of some specific space can encourage people to do something different in their daily life. We have created spaces which don’t force people to do the same activities over and over again, but allow or encourage people to do something different. It depends of course on the set conditions or characteristics of the client. The final product and its final appearance is different between each house but the fundamental basics of these houses is respect for human positiveness and respect for the positive diversity of our life.

JS: Why do your buildings remind us of trees?

SF: This relates to my childhood memories and my architectural thinking between nature and architecture. As a child, I grew up in nature close to a forest in which I played. For me, the forest is not a huge forest but a cosy human forest. My games would lead me to choose different branches to climb or areas which sheltered and protected me or, I’d venture into open spaces – open fields to play in. These were choices, what I liked and beyond. This is the basic or ideal model of architecture or ideal model of human activity because a forest or trees are always allowing/inspiring us to do something different, something new and exciting… promoting our human instincts. If you can create architecture like a forest, not visually like a forest or the actual tree, but the relationship or form or experience of this architecture which is close to the experience of the climbing of trees or playing in the forest…

JS: Like the climbing Tower House in Montpellier?

SF: Oh yes, that’s one of the expressions of this, so people living in each of the different branches can have a conversation with others, like a person in the tree in the forest! Those kinds of open relationships are quite inspiring. That for me is one of the archetypes to describe the ideal architecture.

JS: How is it possible to build 200 balconies and 100 pergolas without interrupting the flow of one of the most expressive elements in your constructions which is the flow of light?

SF: That’s like everything, trial and error? For the project in Montpelier I didn’t want to use computer generated repetitions of the balcony but wanted to create more randomness in the balconies because… the rules to create the tree leads me to want to generate an organic algorithm. However if it is applied into architectural forms, it can become a repetition of the same rules. I was not afraid at the time of those fixed rules producing the mathematical shapes which force people to feel they are in the big system in a sense. I enjoyed creating this building outside of the systems, more randomly, relaxing the rules… Each independent balcony could then have its own characteristics and expression. The final result is reminiscent a tree or pineapples or pine cones. It is organic and not a systematic repetition. What is very important to me is that architecture shouldn’t be a big system which forces people to stay within a room but should be more open like a field, where people feel they are as individuals an important and intrinsic part of the characteristics of the entirety of space.

JS: Can you talk about your Harvard Lecture where you approach the relationship between nature and architecture as well as the relationship between nature and man-made environments?

SF: The subject has to do with my personal background and the area in Hokkaido where I grew up next to nature. I moved to Tokyo to attend university and of course both cities have completely different environments. Tokyo also has a cosy environment, especially the smaller residential areas or the human scale commercial areas – which offer a feeling of intimacy within a large city. I compared the differences and similarities between my hometown forest and Tokyo with such pleasant residential areas and found that both offer a space made up by many floating pieces. In the forest you have small branches and the tree leaves grow randomly so you feel protected within the forest. It’s not like the protection of closed boundaries but more like an open field which protects you psychologically. The Tokyo situation is visually a bit messy but you have many small artificial pieces floating around like billboards or small canopies or small green pots, or even the electricity cables which randomly create a form of subtle sheltering. If you feel you are within these kinds of light protections but at the same time is an open field (not like a closed protection) you can choose your own way to move around. Tokyo and Hokkaido are visually completely different if we compare artificial environment x natural environment. However, the structure behind it, how the space is created, how space affects the human feelings, is rather similar I feel. This is when I realised that we should not judge the characteristics of nature and human constructions through the visual side of things only, but need to see the structure behind it. We have to see the way the space is and the way in which the environment affects human feelings. These layers can give rise to considering that artefacts human intervention and nature share something and have a mixed coexistence or a good interrelationship. Not only putting the greens on the buildings but the way to make the building itself could be more close to the nature or the way to deal with the greens could be closer to the artefacts. These sorts of interrelationships between nature and architecture are becoming more and more important I think.

JS: In 2016 you won 1st Prize in a competition called “Réinventer Paris” . Paris, the city of Lights! Was this competition a contest to rebuild the 17th Arrondissement?

SF: It was a nice challenge because I really love those Ottoman structures in Paris and the coexistence of Haussmann and the Paris before Haussmann Ottoman. They are interacting with each other to create a good range of human life and the dynamics of common situations. Our proposal is to create an alternative which will coexist with the wonderful historical Paris but adding some new interpretations or new values. Our proposal follows the regulations around height and respects the city’s historical architecture. We introduced forests on top of the buildings and made them look like a boat as well as a lot of greenery at the bottom of the buildings.. We also created green areas as much as possible planting urban forests leading to a beautiful contrast between architecture and nature. That was the challenge: to re-interpret the beauty, meaning and importance of the historical city of Paris. At the same time to trial it adding new values giving rise to a new coexistences and harmony, maybe even contrasting the harmony between history and the future. It is a respectful project towards historical Paris and a proposal for the future. I love Paris, I really love the challenge of building on the complexity and diversity of the city with a clear vision as to where we want to go. Because of my love and respect towards this city I am also adding new values to its environment.

JS: Please define your sky mountain Haikou Bay House!

SF: That was kind of an interesting project. At the very beginning we didn’t have the specific sight boundary and we didn’t have the specific program but they wanted to have something special which made the special surrounding characteristics of the neighbourhood enhance. The location is an area facing the beautiful bay where the sunset is really wonderful. It was rather a big open field. We liked to create not just architecture but the coexistence between architecture and the landscape and the plaza as a pathway for the people to observe the landscape. If we had just simply placed the independent building on sight, I felt we would not have related to the sight conditions. If it is an open field the independent building would have been too separated from the surrounding. If the building is iconic, the separation gets even more obvious. I’d liked to created a building melting to the landscape but it doesn’t vanishes. The building itself is getting stronger characteristics because it is out of the landscape and at the same time melts into the landscape. The entire sight and the entire surroundings itself has its mountain like characteristics. That was our trial and as time evolves I am becoming more interested in going beyond boundaries between architecture and the landscape or between architecture and the street/pathway or between the architecture and the plaza. All of them are the place for the human activity. We should not define nor make our design field within the architecture like architectural landscaping. Creating the pathway or the street and their entire platforms is in a plaza for ranges of human activity should be well integrated within the special design. This project is one of my trials to go beyond the boundaries of the building.

JS: What does materials like glass, sand, recycled concrete, steel, resin and water integrate when you plan your houses or buildings?

SF: The importance of materiality for me is getting more and more serious along the years. For example, 15 years ago when we designed the House N which is made by concrete, the concrete was a common material. Recently I feel specially in my Paris office, the increased importance to seriously think about how we can use those sustainable materials or recycled materials to contribute to a more sustainable environment. Timber materials have become more important for us specially recently because the wood construction is being pushed not only for smaller scale but also larger scales since it is a sustainable material. For me, its various use relates to the tradition of the Japanese architecture. A historical tradition of more than one thousand years. If you compare the historical and the contemporary Japanese architecture, they are quite different. We have to think of how to bridge the traditions to the latest or the future wooden constructions learning it’s important history and project some new ideas to the future that is really wonderful. One big trial related to this subject is happening in Osaka where I am doing the master plan and designing the huge wooden construction ring rough for the Osaka 2025 Expo starting next April. There is the need of a main circulation part protected from the rain and to the strong sunlight and also have a nice viewing platform for the people’s view of the surrounding. We proposed the brown rig which has about 650 meter diameter and 30 meter wide and 12 to 20 meter high. It is a huge almost 60 thousand square meter construction. We are trying to create this kind of huge construction by a mass timber construction inspired by the Japanese tradition of combining the cons/bolts and the beams and of course updated according to the latest regulations, mixing the wooden construction and metal joints together. It is easy to construct, easy to assemble and easy to dismantle and easy to be transported some place else after the expo. It is our first experience to apply wood to a huge such construction structure which is globally one of the largest of its kind. It has quite an important meaning to me. I am learning how we can apply these materials in constructions of such larger scales. It is providing a lot of new knowledge and inspiration. Recently we have been intensifying the use of sustainable and recycled materials in smaller and medium constructions as well. In the case of concrete, we are interested in creating low carbon concrete and in the case of steel and specially aluminum materials, we are interested in improving the technologies and new updates of their use. It is a quite important and exciting moment because the new materiality is happening like the starting point of the modern architecture when concrete and large glass was being initially used. That was back then also an excitement of new conventions of the materiality. Now is the time where we are facing huge changes of the materiality of the 21st century. It means we can create some drastically new architecture expressions.

JS: There is a journalist Andrew Ayers, who interviewed you on his 2022 article about you piling up glass boxes, who writes: “If, as Churchill declared when rebuilding the bombed-out House of Commons, “We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us”, what kind of “future leaders” will HSG Square shape? Dare we hope they’ll be touched by a dash of divine grace?” The article was published in 2022 when your Square building was inaugurated and he asks what kind of future leaders will the divine grace of your architecture shape.

I go a bit further! My question to you is why did you decide to become an architect?

SF: (laughs) Wow! There wasn’t a clear reason. I don’t remember such a special moment when I really decided to become an architect. It was no existential or intentionality following those small decisions to get into the architecture scope. Let me explain a little bit. From my childhood days I really loved to make and build things using paper. When I was around 12 years old I was a big fan of The Beatles. I really loved those kind of innovations and the creation of something new. Not only creating physical things but the process of innovating. My father was a Doctor but was also an artist painter and sculptor. He had many books about contemporary art and I bumped into a book about Antonio Gaudi which made me recognise that the architecture design is also part of the creation. Before that I didn’t recognise painting, sculpting and composing music as part of a creation process similar to architecture design. At that moment I realised the similarities of their creative activity. Still it wasn’t the moment I decided to become an architect. It was too extreme. In high school I was more interested in Physics and Einstein inventions. I was really fascinated by creating something new. The creation of the conceptual theory of physics. I was really fascinated by that. When I entered the university I was more interested in learning and pursuing physics or mathematics. However when I joint the first physics class I realised how difficult the professional physics was for me and I couldn’t understand anything about the subject nor what they were talking about… even though they were speaking Japanese, I couldn’t understand anything. I then realised this was far different from what I imagined. After one and a half year at the University, I had to decide which classes to visit. I wasn’t very serious about choosing the architecture design but casually or accidentally I ended up choosing it. Of course I thought about Antonio Gaudi and I also thought about how I loved making things and I was reading a lot about art. Finally I chose architectural classes. The first class was about Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. At that moment, in a state of shock, surprised and fascinated, I knew for the first time about their creation. I loved their works and the fact that they invented the modern architecture. Just like the Einstein Theory. That’s when I seriously headed into architecture. It was a class of 60 students and it seemed that I did better than most of them. My works of small pavilions and small buildings seemed like I had some talent. It is a process without no particular reason but several accidental and unexpected situations which happily led me into where I am today.

JS: In that case can you tell us a bit of the meaning of music and painting in your life?

SF: I am not a good musician nor a good painter. I love listening to music like The Beatles, Bob Dylan and also several piano compositions by JS Bach. I am not listening widely but rather specific music. It was always the structure behind it or the older and the Chaos that interest me. After learning architecture I was also interested in a Japanese composer called Tōru Takemitsu who struggled to find the mixtures of Japanese tradition and the modern music. His struggles are similar to our struggle of the Japanese people’s understanding of modern architecture or contemporary architecture. How to understand the traditions and the mix the traditional eastern culture and the western modern architecture.

As for paintings, I love saying the period of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, the older field of the art or science, the amazing innovative period at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century interest me. Of course Einstein was also part of that as well as Picasso or all the creative genres with their respective creative activities. It was an amazing innovative and inventive period. My understanding of this kind of modern art is really related to its innovative period and the relation of the architecture that was happening in that same period.

JS: Why are you mainly using the white colour on your buildings or keeping the original shades of materials? How far the Japanese minimalism painting is influencing your work?

SF: It isn’t a decision to follow the rules of minimalism but more of an unconscious process. It is really and deeply connecting to the colour culture this minimalism or subtleness of the creative activities is always coming out intuitively. At the same time, since I grew up in Hokkaido, which is the field of nature and the field of snow where it snows almost for a period of four to five months. Hokkaido is almost 1/3 of the year covered by snow and is really cold. That’s where I grew up. I realised that white is not just white but white looks different and reflects the subtle changes of the light or the subtle changes of the atmosphere time by time. When I use white is not just the choice of the colour but more the choice of the phenomena or, the situation which is always reflecting and changing time after time. Even the psychological reflection of each independent persons. White is relating to Japanese culture but also to my personal background.

JS: Could you say that building the Museum House of Music in Budapest and the Square at the University of St.Gallen were ground braking moments in your career?

SF: Both of them are quite important buildings for us and for me. The situations, project programs and visually they are completely different. For Budapest, the building is in the middle of the forest of a huge park. How we create the architecture deeply relating to the nature is clearly expressed In this project. The Museum is almost hidden and the floating roof is like a full structure above you don’t see because it is always behind the trees. Only the feeling is there. The ceiling is made by light gold metal leaves which creates a beautiful contrast between nature and architecture. At the same time it creates a beautiful integration and melts between nature and artefacts. Finally it is a quite symbolic place for the people in Budapest and in Hungary because Music lies in their heart. A place reserved to Music deeply immersed in the forest is modest but quite symbolic and of good sensation. How to continue instigating a basic fundamental experience between nature and artefacts in its architecture, I realised after almost 10 years of the process, is really impressive. Every time I visit the Museum the visitors look so happy. The Museum was designed to be half part of the park and half part of the buildings. That dynamic between the park and the building is almost blurry. The people are casually moving around. The open spaces are sometimes being used for performances. This building is the place for music and the life.

As of The Square, it is a trial to create such creative interrelationships between the people and the people who influence each other intentionally or sometimes unintentionally. The real creative learning of the future is proposed. It is like an open field of floating platforms. Through the atriums, it looks quite casual but at the same time it is made by the grid… It has this fun feelings of the older. The beautiful balance is on the casual atmosphere and the feelings of the older as well the three dimensional interrelationships is really happening because of its openness and its playful staircases. It makes people happy because it isn’t a space of rigidness. It’s more like a playful interaction between people and people or people and the spaces. It is like one of the models I really like to propose the way I explained in the beginning of the interview: let people be encouraged by the space to have unexpected interrelationships between each other or relationships to the surrounding nature. People can choose where they are, they can choose to be connected and sometimes they can feel encouraged or be inspired to do something beyond their imagination. Those kind of open field is quite an important archetype for me. The Square is one of the realisations of this archetype.

JS: How could you condense the three concepts given at the time of the HSG competition:

– the railroad station (walk and immediately orient yourself)

– the workshop (open flexible spaces)

– the cloister (a place or promenade for thinking aloud)

SF: Actually it was related to the process at the very beginning, they liked to have such a flexibility of the activity. In the very beginning I was thinking of this huge walk space which is the railroad station where everything is possible. I thought if the space is just a huge space, everything is possible but nobody was inspired by it, its just too open and just a space. Some kind of structure is needed I felt which creates some kind of feelings of the older and the human scale but at the same time, we couldn’t feel connecting to the other places. It’s just the Chaos. The cloister idea appeared because it is St.Gallen, the place of the monastery. The monastery is one of the historical references. The monastery is one of the origins of the University of St Gallen or of learning places. The cloister is a quiet symbolic place. The monastery/cloister is a static with quiet spaces where people walk around. If we can read this cloister in a more dynamic experience, this might be quite exciting re-interpretation of the learning future of learning spaces. If it is three dimensional, we have three levels through this central atrium, we can have cross interrelationships of the different platforms. That might mean dynamic experiences for the Students. A three dimensional cloister but not static but more dynamic. I felt it could be the place where many different activities are happening independently but many different things are influencing each other unexpectedly. Those kind of unexpected encounters of the different activities or different conversations or different atmospheres could create and inspire something new. I felt it as the creation of the coming future and the new way of learning. It was the simple process of how we achieved the three dimensional cloister around the central atrium. We are still keeping the flexibility, not the big flexibility of the train station but more like some older flexibility or the good balances of coexistence of the flexibility and the open space. Both of them are linked by the concept of this three dimensional cloister.

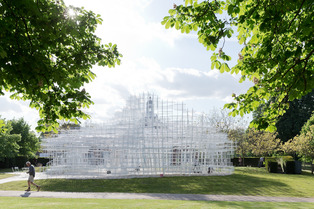

JS: What is the parallel between your Pavilion at the Serpentine in 2013 and the National Pavilion in Osaka in 2025?

SF: In Osaka the Expo like mentioned before, doing the circle ring and I didn’t design the National Pavilion, it is a different designer. The Serpentine Pavillon was the trial to create such as space where multiple things are happening simultaneously and interacting to each other. The space is also interacting to each other. It was a quite dynamic interactive experience. I myself was really fascinated by that. The space and people in the nature had these kinds of interactions. That was really amazing. For Osaka, when I talk about the big ring, it is like a common ground ring but it is a huge scale, a different scale from the Serpentine. Both structures allow people to interact as they like. Regarding the ring, the shape of the circle is a strong shape but each independent area is made by the big frames of the wooden construction. It isn’t a homogeneous grid. We are intending to make the several types of the different grid frames happening place by place. It is more like an open field for people and at the same time people can go up to the roof. I created a bank. The rooftop is not flat. Inside is a 10 meter wide round flat. The slope in the sections is going up. I made this bank because of the roof top and because of this bank, this huge ring will cut out the entire sky as one circular shape ring of the blue sky or a cloudy sky. That is the wonderful experience to recognise the entire sky as one entity. It looks like another cloud is floating above you, and this experiences connecting with the coexistence between the Serpentine pavilion and this grand ring ring… in case of the Serpentine, because it was in a small scale, more experiments around these building, together with the independent spaces is making the good coexistence of this huge entire entity. The independent different things are interacting to each other. In case of the Serpentine, everything looked like a place by place and not an experience of the entire something. In case of the Expo, on one hand we have such a huge experience of the sky! but at the same time is not just a one experience but each different experience is happening. These are the differences and similarities of Osaka expo ring and the Serpentine pavilion. Both are like clouds and the sky in the nature relating to such large phenomena.

JS: Magical words in your architecture making the correlation to the Torch Tower in Tokyo:

imaginary / sustainability / diversity /choices / transparency / functionality /

primitive future and

zen buddhism because Zen is essentially a practice, an experience, not a theory or dogma.

Do you agree and are these elements part of your architectural practice?

SF: I am not a specialist of Zen but being a Japanese person, yes I agree because Zen is not a trial, is not a minimal something. It is the attitude and the understanding world. In that sense, yes, we can say our architecture has some relation to Zen, but it is not a minimal or a simple something. I feel that Zen for myself, is accepting such a wonderful diversity of the entire world keeping some kind of consistency. It is the coexistence of this wonderful diversity and the simplicity in a sense. Not just a simple Not just the chaos but both of them are like a coexistence together at the same time. It may sound like a contradiction but those kinds of the contradictional attitude is like a Zen I feel. The attitude to design a house as I explained in the beginning of this interview is also related to Zen. We like to respect such an unexpected behaviour of the people in our life I like to respect a lot. At the same time it doesn’t mean chaos. It is always like one architecture which is not limiting the peoples behaviour. We make the architecture and then we make open possibilities for the peoples lives. It may sound a bit contradictional because we are limiting by making the architecture. It is more like opening the possibilities and potentials of our live.

JS: Do you understand structuralism as the starting point to your architectural projects?

SF: I am not sure I fully understand it but I feeling I am sharing this kind of feelings and also, but I am not really sure.

JS: Isn’t this related to you reinventing structuralism in Japan?

SF: I am always wondering about the structural physical and then the conceptual in a sense. Structure may force people to be limited but at the same time, the structure could open peoples’ possibilities to behave in a different way. In that sense, yes, I like to create those kind of structure which allow people to be open. At the same time, I am always wondering if Structure is needed. It could be more open without structure, or bring new understanding for the structure. There was like the brother tendencies to use those kind of fragmentations. The organisation of these fragments, I was thinking of the reorganisation of them and open the possibilities of the peoples behaviours. Recently I think, the fragmentation itself their risk of limiting peoples’ behaviours. It is getting a bit more fluid in a sense. Within the fluidity we can create a structure. As of myself, I am still wondering. Those kind of structures made by fragmentations are interesting for me but is getting more fluid. The very elementary thinking of structuralism has been changing and through my trial.

JS: How do you relate to existing buildings and their transformation and how about your project collaboration with Jan de Vyldern?

SF: Recently we are doing those kind of renovation and transformation of existing buildings and it is really interesting because is relating to the history and the future and then the structure and fluidity as well as the materiality of an existing building. Existing buildings has its own materiality. It is very interesting how to re-understand the materiality of existing buildings. The amount of projects for renovations and refurbishments are increasing. The reinterpretation of historical buildings is happening. In a sense if you make new buildings in an existing context, it is already the renovation of the context itself. In that sense new building and the refurbishment or renovation of the old buildings have a continuity to re-understand the context.

JS: Are the suspended gardens in Paris also the renovation of existing buildings?

SF: Yes, that’s true. It was a reinterpretation of Paris. The building itself is a new building. We re-interpretation of historical Paris. If you have a wider viewpoint about new buildings it is already part of the renovation of the existing context.

JS: Thank you so much Sou!

SF: I really enjoyed the conversation with you.

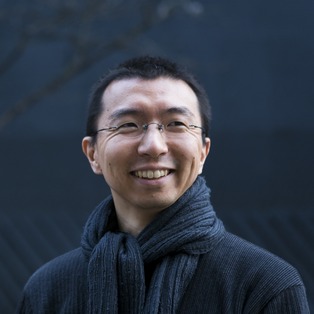

Sou Fujimoto was born in Hokkaido in 1971. Graduated from the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering at Tokyo University, he established Sou Fujimoto Architects in 2000. In 2018, he won two International Competitions for the Village Vertical in site of Rosny-sous-Bois and for the HSG Learning Center in St. Gallen. In 2017, he was the winner of two International Competitions, for the Nice Meridia and the Floating Gardens in Brussels. In 2016, he has won the 1st prize for “Pershing”, one of the sites in the French competition called ‘Réinventer Paris’, following the victories in the Invited International Competition for the New Learning Center at Paris-Saclay’s Ecole Polytechnique and the International Competition for the Second Folly of Montpellier in 2014. In 2013 he became the youngest architect to design the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion in London. His notable works include; “Serpentine Gallery Pavilion 2013” (2013), “House NA” (2011), “Musashino Art University Museum & Library” (2010), “Final Wooden House”(2008), “House N” (2008) and many more.

architecturalrecord.com designboom.com