«Human Rights Watch»

Von Julieta Schildknecht

Kenneth Roth is the executive director of Human Rights Watch, which operates in more than 90 countries. Interview about human rights issues related to education, technology and art during our global Covid pandemic.

Prior to joining Human Rights Watch in 1987, Roth served as a federal prosecutor in New York and for the Iran-Contra investigation in Washington, DC. A graduate of Yale Law School and Brown University, Roth has conducted numerous human rights investigations and missions around the world. He has written extensively on a wide range of human rights abuses, devoting special attention to issues of international justice, counterterrorism, the foreign policies of the major powers, and the work of the United Nations.

Julieta Schildknecht: Education has been an important theme in your family as well as for your wife Dr. Annie Sparrow who was playing an important role as an adviser to the WHO (World Health Organisation) director general regarding the pandemic. I would like to therefore ask you how important is Education in terms of Human Rights?

Ken Roth: Education is essential to Human Rights because people have to be taught the concept of Rights. I think that the substance of Rights is intuitive. The fact that people don’t want to be discriminated against, that they want to be treated fairly, that they want to be able to speak out and associate with others whom they choose; the fact that people need basic food, housing and health care. Those rights are very intuitive but what requires Education is the concept that these are claims that people have on their government. There are limits to what governments can do to people and duties that governments have towards them. That’s the importance of Education. The other part of Education which is important, is that it is a way of encouraging respect for differences. It is a way of confronting tribalism or exclusionary points of view where there may be a tendency to view people who are different as „others“ – that they are somehow less deserving of the same rights that one wants for oneself. I think that Education can help broaden the perspective to see the common humanity of people who may have certain restrictions or differences.

JS: During the pandemic, your organisation was quite busy protecting key issues that are under threat to change our social environment in a total dependance of the state . Can you please mention these issues and tell us why are they so important for the maintenance of humanity’s well being?

KR: I think the pandemic spotlighted certain inequalities in society and amongpeople who are left behind. This was something that preceded the pandemic, obviously, but we saw the pandemic attack more vulnerable populations and exploit that inequality. There was a good side and a bad side to this development. The bad side is that people suffered and the good side is that it made everybody much more aware of these social discrepancies and unfairnesses in society. I think it has kindled a greater determination to address them. There is much greater awareness now of inequality and the need to try to address it . The pandemic also gave rise to some of the worse impulses among political leaders. People like Viktor Orban, the Hungarian prime-minister, used the pandemic as an excuse to seize the ditactorial power for him to rule by decree. Many governments censored critics, which is highly detrimental to public health. Public health requires free debate, free exchange of information, freedom to alert us to public health threats. Censorship impedes that.

JS: You wrote an article about the Zombie Democracies. Is this related to this threat?

KR: This is related to a different issue. What we saw leadesr such as President Sissi in Egypt, Prime-Minister Modi in India, and President Erdogan in Turkey imprisoning Doctors and other public health officials who would either raise inconvenient threats posed by Covid-19 or criticise the government’s response. Such censorship is a sure way to help the pandemic win. This was worse in Wuhan in the beginning of the pandemic when the Chinese government censored the doctors for three weeks who were trying warn us that Covid spread from person to person. The Chinese government wanted us to believe in the beginning that Covid came exclusively from some animal in the Wuhan market. That of course wasn’t true, but during those three weeks of censorship, millions of people fled Wuhan or traveled through it, and the virus went global. These are illustrations of how damaging censorship can be…

Now, the issue to Zombie Democracies is something a bit different. We’ve seen for many years how Autocrats try to manage Democracy. They will try to impede the opposition, they will try to control the media, they’ll try to limit opposition parties, all with the aim of still having an Election but tilting the ballot, tilting the playing field to make it look more likely that the autocrat will win.

What we’ve seen over the last year isa series of public demonstrations where people are clearly not putting up with this managed Democracy anymore. They want real Democracy. The Autocrats in turn are increasingly getting rid of even the facade of a fair Election. They are tilting the plain field so radically that what is left is a Zombie Democracy – the walking dead of democracies, elections with zero credibility.

JS: During the pandemic, wasn’t that also an excuse to increase the power of many governments?

KR: Of the Zombie Democracy?

JS: Yes…

KR: The Zombie Democracies are what leaders like Putin in Russia or Ortega in Nicaragua resort to when they fear they will lose even a managed Election. They shut down any possibility of political competition. Certainly the unhappiness of how the leaders dealt with the pandemic fuels the public discontent with these Autocrats. Some of them, rather than accept the reality that even in a managed Democracy they are likely to loose an Election, are turning to Zombie Democracies — getting rid of any pretence of a fair Election. This is what is happening.

JS: Lets talk about digitalisation, communication, media and data protection. Where and how important is the understanding of Law in this field and our human rights?

KR: The Law is just catching up with our digital society. I think we have to admit the Law is way behind. The digitisation has moved so quickly that the Law is trying to figure out how to protect our privacy, how to control the social media platforms, how to deal with artificial intelligence. For the most part governments have done little or nothing. There is really hardly any Law right now on artificial intelligence or on certain permutations such as in facial recognition technology. There is much talk about how the social media platforms are spreading divisiveness, hate speech, disinformation but there is no good legislation yet in how to address them. On privacy, Europe came up with a GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) which is a step in the right direction, but it has been reduced to a kind of check-the-box exercise. There are cases where a website pops up with some kind of consent issue and most people just give the consent because they don’t want to read or even find the fine print on consent So even there, the media and digital companies are vacuuming up our data with very little meaningful consent from us to relinquish our privacy.

JS: This bring us to a different kind of wealth: the data wealth, right?

KR: Of course, the data is not just our personal information, it is also value because the data can be sold to advertisers who then try to manipulate us in a more refined way based on what the data shows about how we think, how we perceive things or what our preferences are. Yes, the data is behind a much more sophisticated form of manipulation. It is far more refined than when we turn on the TV and get in whatever random ads are shown for the broad demographic of people who watch a particular show. With social media, it is possible to serve up very finely tuned ads geared to what the data shows you want, what you think, which allows a much greater manipulation — not simply for commercial purposes but also for political purposes. We’ve seen this with politicians who are using the same tools to try to move the public, quite often toward hatred, toward divisiveness.

JS: How can we operate towards these societal challenges thinking of – for instance – TikTok?

KR: TikTok has a separate problem being a social media platform owned by a Chinese company. Whenever there is a Chinese company involved, there is no capacity to resist Beijing’s effort to collect that data. That’s the problem with Huawei. There is no way a Chinese company can say no to the Chinese government seeking its data.That is an added problem of TikTok. It the latest social media craze, particularly popular with young people. It can be an innocuous, showing people clever videos. But it obviously has the same capacity to manipulate because their algorithms choose which video to recommend. Those algorithms are based on what is known about who you are from the data collected via TikTok or other devices.

JS: How about the creepy campaigns of children or adolescents committing suicide because of strange jokes or contests?

KR: This is a broader problem.

JS: Yes, like the teacher at NYU being beaten because of TikTok’s reactions?

KR: I think we have seen with a number of social media platforms that have users of particular vulnerability. Whether there is bullying or social pressure, Facebook just did its own internal survey showing that Instagram makes many adolescent girls feel inferior. They see their friends putting up this perfect version of their lives and they feel inadequate by comparison. Facebook had that information but basically doesn’t seem to have dealt with it.

JS: In case of TikTok, are they going to be challenged by the Congress or are they coming for public hearing or how can we operate in face of such challenges? Is it too late or do we have time to react and transform?

KR: Trump was going after TikTok in particular. I don’t think the US Congress today is going to target TikTok separately from other social media platforms. Is it too late? No! It’s late but it’s not too late. There is still a lot that can be done to rein in some of the evils of these platforms.

JS: There are professors teaching in the field of cultural issues who say “Change never ends”. How fast then do we adapt and update legal concepts related to human rights?

KR: Many of the core human rights were first codified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 and they are still very relevant. Most human rights don’t need updating at all. The broad principles of freedom of expression, freedom of association, fair trials, prohibitions against torture, or summary execution, these are all perennials. They don’t need updating, they need respect. There are certain areas where the world has changed. What the right of privacy meant let‘s say 20 years ago, where the issue was whether a police officer could snoop behind your drapes, looking inside your house, That’s an old fashioned understanding of what privacy is today. That can still be a problem but privacy today presents much more sophisticated problems. Is it an invasion of your privacy for a communications company to track your movements simply because you cary your mobile phone with you? You can completely reconstruct somebody‘s life just by using their mobile location data. In a traditional view, people would say, you were outside, you were in public, you have no right to privacy outside. That was in an era where the police would have to follow you to know what you were doing and the police didn’t have the capacity to follow more than a handful of people. Today everybody can be followed automatically via their mobile phones. It is highly intrusive to reconstruct your life through your location data even if technically you are outside or out of your home. We need to update the concept of privacy in this context to make clear that it is an intrusion, it is a violation of our privacy to use these more modern electronic technics to delve into our private life. Even though it’s outside their home, we need a kind of a concept of the right of privacy in public which I think the public demands these days but the Law is only beginning to catch up with.

JS: In this case are we talking about historical taboos or cultural disparities that vary from country to country?

KR: The privacy issue is not about a taboo, it is just about a concept catching up with modern technology, but I think what you are referring to now is that there are cultural differences which probably are most acute around freedom of religion, the rights of women and certain sexual rights. This is where you see governments asserting cultural differences. The Taliban says it is our culture to suppress women and leave her at home and not get her educated… Or you get various governments saying it is not in our culture to allow gay people even though there have been gay people in their society forever. Often the law against it was a colonial implant… Or you see governments saying it is a violation of their culture to switch your religion or to say something bad about your religion… or to prostletyze ,trying to encourage somebody else to join your religion.

In all of these cases, there are people in those societies that are actively trying to assert their rights. It is the afghan women who want the right to leave home by themselves, who want the right to go to school, not a foreign imposition.

JS: or drive cars…

KR: or drive cars in Saudi Arabia or go to a football game in Iran. Nobody has to tell the women in these societies you should assert your rights… they want these rights. The assertion that is not our culture for women to be treated equally, is a very convenient thing for the men in charge to say. They shouldn’t pretend its their culture, they should just recognise there is just a power play going on with the men in that society. At least the ones who are in charge. The Taliban today in Afghanistan, they want women rights suppressed and then they use culture as an excuse to justify that suppression.

JS: On your annual report that was boycotted in Hong Kong, there is a paragraph in the article entitled “Addressing Today’s Urgent Challenges – Building the Future we want to see”. Can you please mention what are your organisation’s actual priorities?

KR: We cover the entire world. We work regularly in a 100 countries. We address full range of Human Rights. It’s hard to reduce everything to one or two priorities. Obviously today if you look into what are the big threats to human rights, the Chinese government which was very much the focus of that report you mentioned, is an extremely powerful force that is trying to undermine worldwide human rights standards. The Chinese communist party shows no respect for human rights. In their view all that matters is building their GDP (Gross Domestic Product) so they can assert that their economy is growing. They don’t want to permit anybody to criticise Xi Jinping. They don’t want to permit anybody to organise independently of the communist party. They are now in the process of detaining a million Uyghur and other Turkcic Muslims in Xinjiang to force them to abandon islam, their culture and their language. Of course a government like that doesn’t want actively enforced human rights standards. It is devoting enormous effort to undermining those standards.

They had a one trillion dollar effort called the “ Belt and Road Initiative” which was basically an effort to buy friends to undermine human rights. That is an enormous threat. It is easy enough to see through it. The fact that Chinese economy is growing says nothing about how ordinary people are treated in China. Indeed you have these vast rural populations that are utterly left behind, they can’t even move to a city and get education for their children who are typicaly left back in their rural areas. There are all kinds of injustices within China. They don’t want you to look into that. They just want you to look at the size of their economy.

For that matter, if you want to know how China operates abroad, they don’t want you to look at the fact that these development projects are really just often debt traps where they give out commercial rate loans, not even concessional loans. They seize property if the government defaults on these loans. The loans have no transparency, which encourages corruption by the local elites. They serve China’s needs for resources but not the local populations needs for genuine development. There is a real need to scrutinise China’s conduct at home and abroad to undercut this view of this dictatorial system as somehow superior to a system based on human rights and rights-based on Democracy.

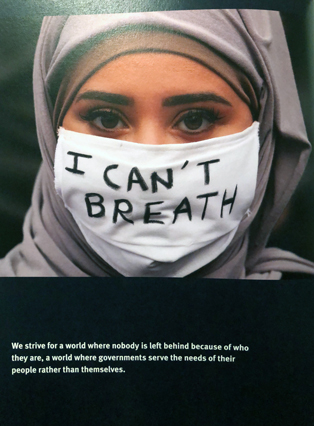

JS: On the picture taken in 2020 by Nicolas Tucat, we see a muslim young lady wearing a white mask with the following handwritten words: “I can’t breath”. Based on this picture I ask you: what now? What are the real pictures of increasing poverty during the pandemic telling us?

KR: I think that the original concept of that photograph is related to racial injustice and police violence in the United States against Black americans. The fact that this a young muslim women shows us that persecution takes place in different forms. The picture was taken during a demonstration against racism and police brutality in Bordeaux, France. The French government has been very tough on Islam. In the name of trying to rein in Islamic extremism, it is controlling various forms of Muslim religious practice. Indeed Marine Le Pen‘s Party is building an entire political challenge on essentially an anti-Muslim platform.

JS: What now? What are we to do in face of all these racist circumstances and in terms of human rights? Are we to continue to protest and write more about these issues? How to proceed?

KR: There is no single answer to that. Obviously ongoing protests are important. It is also important to document how racism plays out, such as looking at how police behave. Who are they stopping for searches, how are they using force, how are they deploying their resources, and is there a discrepancy in the use of force depending on who the person is before them? Are they targeting areas where there are more racial minorities? There is no single answer. It is important for us to both keep the public condemnations coming without forgetting to scrutinise to make sure that we understand how police are acting.Unless we really understand their practice, it will be impossible to monitor whether a change is happening and if there is a need for change.

JS: Based on your answer, where or how do we find a balance between values and missions when narratives in media operate falsehood with bias messages?

KR: There have been always media that lie. It has become more pervasive because of social media. In a sense anybody has a platform. There is no longer the major media which serve as a filter for points of view. In a sense the traditional media at least theoretically coudl weed out at certain lies. But today, anybody has access to social media. I don’t think the answer to this is censorship because that introduces a whole new range of problems. I still believe in the truth. An essential defense is publicizing the truth. It’s not going to reach everybody but it is going to reach a critical mass which remains important. I think we’ve also learned that it isn’t enough to portray the dry truth. We have to be creative in how we portray the truth and keeping it compelling. Those who oppose to the truth find clever ways to portray and ehance falsehoods.

JS: How about freedom of speech and human rights would be the next stage, right?

KR: Well, the freedom of speech is essentially a human right. If you can’t speak out against governmental misconduct, you will have a very hard time defending human rights.

JS: How to resist the uncontrollable rising power of state to guarantee freedom of movement in face of climate change?

KR: This is a big issue because climate change is going to force people to move both within their countries and between countries. The ultimate answer is to address climate change but we are not doing a good job in doing that… The critical question is: when climate change renders certain areas inhabitable, how to ensure that people’s rights to basic necessities are respected? This is an issue for both governments and the international community to make sure that these people that are forced off their land and forced away from their home, towns and villages, are received with basic housing, basic healthcare, basic food and basic education. We have to ensure that that’s available even for people who are forced to leave by climate change.

JS: Bertold Brecht wrote in his 1934 book “Threepenny Novel” a passage where the Gangsterboss Machete tells Hawthorne while in prison that Freedom is something intellectual and that thoughts are free. He wrote this book at a time of decadent outrage of wealth and poverty. Could you point similarities we are facing and we are going to be able reconstruct social structures in post pandemic or the economies will have to mainly concentrate forces on data exchange and technology improvements?

KR: What is interesting about the governmental response to the pandemic at last is that governments did things such as providing a social safety net that were quite extraordinary. In the United States in particular where the social safety net is much weaker than in Europe, there were huge amounts of money thrown into that safety net because of Covid with the result that poverty actually decreased in the United States during the pandemic.

The real challenge today is how to maintain that investment beyond the extraordinary challenge of the pandemic. How do you make permanent some of the social welfare innovations that occurred during Covid. Biden’s big reconciliation legislation is filled with social safety improvements that would go a long way to address and reduce poverty. It is unclear yet whether it is going to pass but I suspect it will be adopted in some form. This is the way in which a positive result would have emerged from the pandemic.

JS: There are however other countries like Brazil who are suffering incredibly.

KR: Absolutely…

JS: In Brazil there is an increase of poverty all over the country. The same as in India.

KR: There is obviously huge suffering hardly at this point because of unequal access to vaccines, partly because of denial. You mentioned Brazil. The country is suffering mainly because Bolsonaro thought it was in his political interests to downplay the pandemic. India is going through something very similar because Modi for recent regioanl elections wanted the economy to be flourishing so he decided to pretend that the second Covid wave wasn’t happening — with disastrous results. We really have to look situation by situation to see why is this suffering occuring. Sometimes it is the misconduct of certain politicians and sometimes it is the failure of the international community to address the global inequalities and in these days it is particularly acute around the access to the vaccines.

JS: Based on Vilém Flusser’s Essay “On Doubt” – do you agree if we say existential situations are no longer nihilism but an intrinsic part of artificial intelligence’s new age lifestyle?

KR: For the most part, people are immersed in their real lives, but there is now a virtual dimension to our lives.

JS: Zuckerberg’s Rayban spectacles for instance… or the VR goggles, right?

KR: That gives you more information. It allows us to communicate in a different way… I wouldn’t pretend that that’s a separate reality. The danger of artificial intelligence is really the way that is used. It doesn’t change our experiential reality. If governments use it to allocate social benefits and end up introducing biases through artificial intelligence, which almost always happens, people are getting hurt because they are ineligible for something they need and they have nobody to turn to to challenge the algorithm. In very extreme case, governments are developing so called killer robots — that is to say, fully autonomous lethal weapons that operate on artificial intelligence. There is some programmer that says go find this kind of person to kill them and the weapon goes out and finds those people or what it thinks are those people. There is no human to pull the trigger. That’s dangerous. If you could imagine it was bad enough… I keep thinking back to when Hosni Mubarak, former Egyptian president, sent the police to shoot the demonstrators in the Tharir Square and couldn’t get them to do it. His government collapsed as a result. If he could have sent out killer robots, all the demonstrators would be dead. It shows the danger of these fully autonomous lethal weapons. Human Rights Watch is trying to get them banned and there are quite a few governsents that are interested in banning them but the usual suspects don’t want to including United States, Russia and China.

JS: Simone de Beauvoir wrote an essay called “The Ethics of Ambiguity” where she argues about freedom of existentialism with Jean-Paul Sartre and Merleau-Ponty.She writes:

“Oppression divides the world into two clans: those who enlighten mankind by thrusting it ahead of itself and those who are condemned to mark time hopelessly in order merely to support the collectivity; their life is a pure repetition of mechanical gestures; their leisure is just about sufficient for them to regain their strength; the oppressor feeds himself on their transcendence and refuses to extend by a free recognition. The oppressed has only one solution: to deny the harmony of that mankind from which an attempt is made to exclude him, to prove that he is a man and that he is free by revolting against the tyrants. (…)

When a conservative wishes to show that the proletariat is not oppressed, he declares that the present distribution of wealth is a natural fact and that there is thus no means of rejecting it; and doubtless he has a good case for proving that strictly speaking, he is not stealing from the worker the product of his labour, since the word theft supposes social conventions in other respects authorises this type of exploitation; but what the revolutionary means by this word is that the present regime is a human fact.”

What are the oblique human rights perspectives toward unfair distribution of wealth that happened during the pandemic and the obtuse social distance by many states around the globe?

KR: The whole concept of proletariat is outdated these days because that presumed a world where it was just an issue of the haves and haves not. What we have seen today is that the divide is often cultural and is social. Its about people that are respected or not by the elites. We found that those kinds of social or emotional appeals actually will overcome people’s economic interest. We get people who vote for serving other people’s economic interests just because they feel heard by a politician who is serving those others‘ interests. Are the politiica is speaking to their hatred or to their fears or what have you. I just see the world kind of more complicated then a classic Marxism where is capitalism, an elite, and the proletariat.

JS: Initially Human Rights Watch was named Helsinki Watch was founded post cold-war in 1978 to monitor the Soviet-Union’s compliance with the Helsinki Accord. Going back to Kissinger’s negotiations with Brezhnev, two of the mains discussions discussed were MFN and grain deliveries. How are we doing during the pandemic in terms of geopolitics and basic infra-structural support around the world?

KR: The big failure is in the realm of vaccines because today we are very close to producing the 11 billion vaccines that are estimated as needed to vaccinate the world. The big issue is how to distribute them and more important who is going to pay for that. If you look to the pledges that are coming from the wealthier countries, they are azly compared to the need.

There is an urgent need to address this as a matter of equity but it is also a matter of self-interest because if there are parts of the world where the virus is still running rampant, inevitably, the virus will evolve and one of those variants will circumvent today’s vaccines.

It is in all of our interest to vaccinate as many people as quickly as possible.

JS: Is this going to be helpful or this going to be a change or is it like a long term solution?

KR: So far governments are not treating it with the urgency that it deserves. I think that between the US and the European Union, they’ve been pledging to pay for lets say a maximum of 2 billion doses to be distributed. Which is a relatively small fraction of the 11 billion that are needed.

JS: The pandemic increased a phenomenal empowerment of tech businesses. Creativity became a core asset and art defines geopolitical streams. How will Human Rights Watch monitor freedom abuses toward creators or art schools, universities and art institutions practiced by far right regimes?

KR: Art is a very important form of expression. The artists are so often the most pointed critics of dictators in our realms. Today while the people of Myanmar are brutally suppressed back home, there is artists who are exhibiting in Paris about the junta’s brutality.

You see Ai WeiWei travelling around the world Highlighting the repression in China that his compatriots back home, his fellow artists, cannot express without being arrested. We see this around the world where art is a critical way of making people appreciate the ways in which governments suppress people. Artists also speak to us in a more direct and vivid way than others.

JS: Is it possible that it can become a symbol of far-rights governments?

KR: Of course governments try to co-opt art but they tend to be ineffective because government art is almost toxic. The true artist has an irreverence that is antithetical to government conduct. So I am not super worried about governments supplanting art because they tend to do so in vain.

JS: Would you like to talk about any issue that you think is important?

KR: We covered a lot of territories.

JS: New projects?

KR: Human Rights Watch‘s big priorities are some of the obvious ones: Afghanistan, Mynmar, Xinjiang, Tigray. Those are some of the things that keep me up at night.